An innovative device developed by University of Central Florida and Orlando Health researchers can save doctors critical time during life-or-death operations, like heart surgery.

Their real-time blood monitor provides instant blood analysis to let surgeons know if a deadly problem in many surgeries — blood coagulation — is happening.

Current tests can take up to 30 minutes, which is too long to wait on results when every second counts. This is especially important during surgery on the youngest patients, such as infants.

The researchers’ latest work, published recently in the journal Soft Matter, is a numerical model that quantifies how the device works and adds further validation to its effectiveness.

“Right now, if we want to determine if the blood in a patient undergoing heart surgery is thin enough so that it won’t form clots in the heart-lung machine, we have to draw blood from the patient periodically, throughout the entire operation, and then send it to a laboratory to get tested,” says study co-author William DeCampli, a pediatric cardiac surgeon at Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children.

“There are two problems there,” says DeCampli, who is also a professor of surgery in the Department of Clinical Sciences in UCF’s College of Medicine. “One, we’re drawing blood from a patient periodically, and if this patient is a newborn baby, it doesn’t take much blood drawn to cause the baby to have a problem with blood loss. Secondly, when we send these tests away, it takes time to get the answer back, as much as 20 or 30 minutes. And that’s too long.”

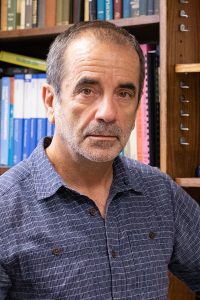

DeCampli has been working with Aristide Dogariu, a Pegasus Professor in UCF’s College of Optics and Photonics, since 2017 to develop the blood monitor. The device has already successfully advanced through one clinical trial and is scheduled for a next clinical trial this year.

The collaboration came about as the result of a meeting at UCF where DeCampli learned about Dogariu’s work using light scattering from a laser to measure the thickness of various fluids and mixtures.

Since then, the optics-based blood monitor has moved through in-lab testing and then a successful clinical trial, the results of which were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

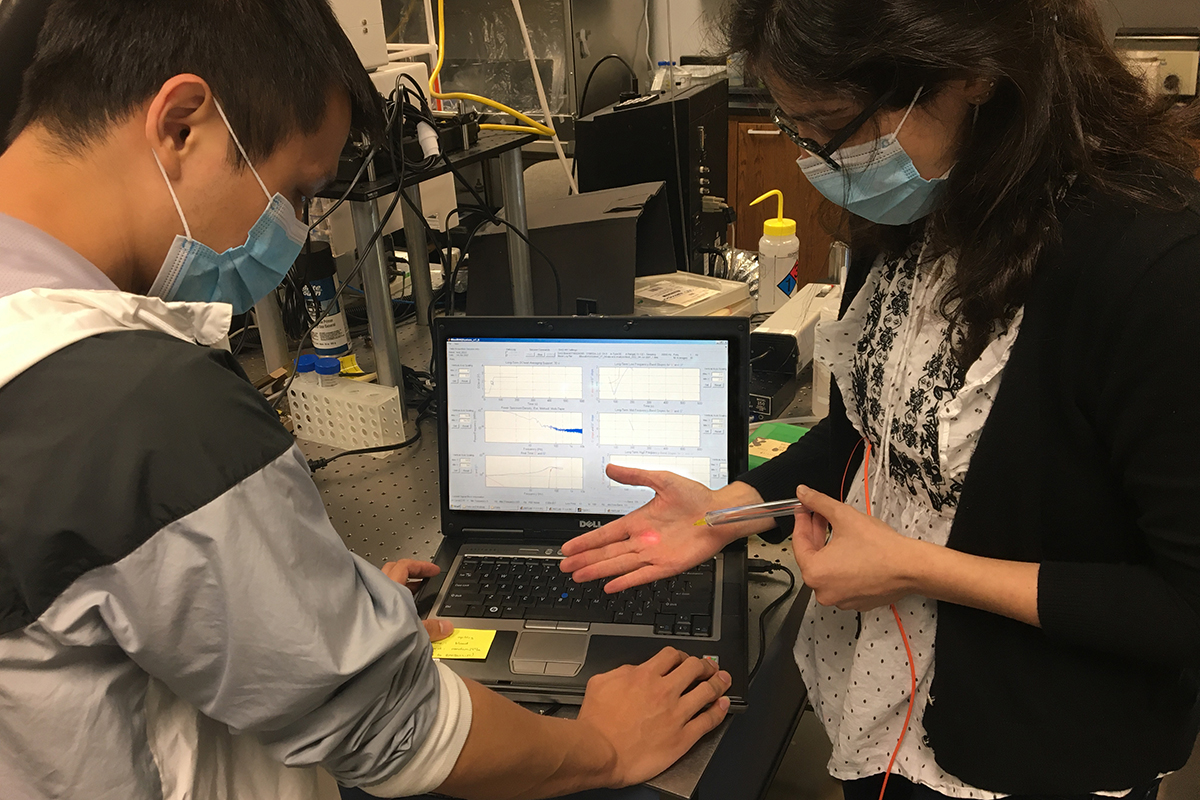

The monitor uses an extremely small optical fiber that’s a fraction of a millimeter in diameter to assess the status of the blood and can be inserted directly into the tubes of a heart-lung machine or in a catheter, without having to withdraw blood from the patient.

In the latest study, the researchers demonstrated that they could quantify the mechanical properties of plasma that surrounds the red blood cells, which is key to describing the light fluctuations they use to determine if blood is beginning to coagulate.

Their model was validated by optical microrheology measurements in laboratory-controlled conditions and in clinical environments involving both natural, intrinsic processes and external interventions.

“The really nice thing about this current study is that Dr. Dogariu and his team were able to show that there is actually a fairly straightforward relationship between the measurements and two fundamental quantities that characterize the mechanical behavior of blood,” DeCampli says.

This is essential information that can be used as the technology moves its way toward widespread release, Dogariu says.

“We developed a model that has been essentially confirmed by the experimental results that we have collected,” he says. “We had the measurements that appear to be quite sensitive to real transformations in the bloodstream, but now we can put numbers to those changes.”

The work allows the researchers to, for the first time, relate their measurements to what was actually happening to the blood and explain the changes in the way that red blood cells “jiggle” around in the blood stream.

“This is what we consider to be the next level in the development of this concept,” Dogariu says.

The researchers’ next clinical trial will take place with pediatric patients, and then they hope to move into a series of clinical trials with adults. With continued success and funding, the researchers hope to see the blood monitor become available within the next five to seven years.

Study co-authors also included Jose Rafael Guzman-Sepulveda, a graduate of UCF’s College of Optics and Photonics doctoral program and now a researcher with the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute in Mexico; and Mahed Batarseh and Ruitao Wu, graduate research assistants in UCF’s College of Optics and Photonics.

The research was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Dogariu received his doctoral degree in engineering from Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan, and joined UCF in 1997.

DeCampli received his doctoral degree in astrophysics from Harvard University and his doctor of medicine degree from the University of Miami. He completed residency in cardiac surgery at Stanford University and joined UCF’s College of Medicine in 2009.